Every week in my practice, I have a conversation that surprises my patients. They sit in the chair, point to a cavity on the digital x-ray, and insist they do not eat sweets. They are telling the truth, yet the decay is undeniable. When we review their diet, the culprit is almost always savory, starchy comfort food. This brings us to the concept of pasta in dental terms. To a dentist, a bowl of fettuccine is not just dinner.

Table of Contents

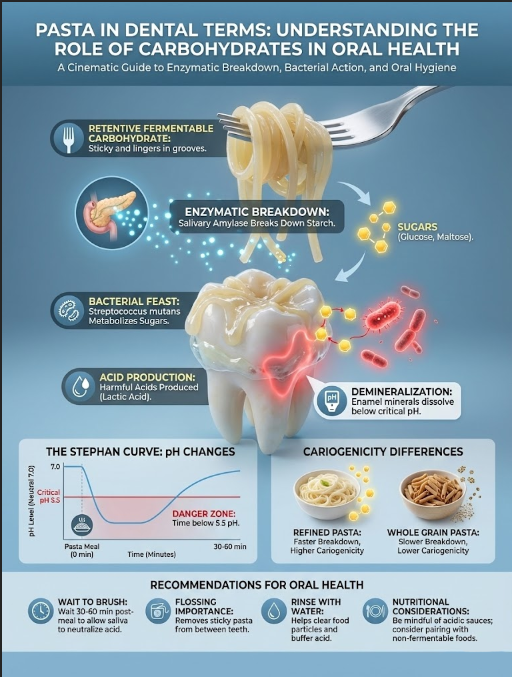

It is a retentive fermentable carbohydrate. Chemically speaking, it behaves almost exactly like sugar once it enters the oral environment. The difference lies in how it sticks to the tooth surface. We cannot simply categorize foods as “sweet” or “savory” when discussing oral biology. We must look at how they interact with the biochemistry of the mouth.

Quick Answer: What is “Pasta in Dental Terms”?

Pasta in dental terms is defined as a complex polysaccharide that undergoes rapid starch hydrolysis in the mouth. When mixed with saliva, enzymes break the starch down into simple sugars like maltose and glucose. Because cooked pasta becomes a gelatinous paste, it adheres to the tooth surface (retention). This fuels acidogenic bacteria within the dental biofilm to produce lactic acid. This acid dissolves enamel long after the meal is finished.

While pasta is a staple of the Western diet, its impact on your teeth is dictated by three biological factors. These are oral clearance time, the Stephan Curve, and the composition of your dental biofilm. In this comprehensive guide, we will examine the journey of pasta from the plate to the pellicle. We will define exactly how to enjoy this food without compromising your enamel.

Key Statistics: Carbohydrates and Caries

- pH 5.5: The critical threshold where enamel begins to demineralize (dissolve).

- 20-40 Minutes: The average time it takes for saliva to neutralize acid after eating starch.

- 90% of Humans: Harbor Streptococcus mutans, the bacteria primarily responsible for processing starches into cavities.

- 45-60 Minutes: The recommended wait time before brushing after an acidic meal to prevent abrasion.

- Double Retention: Cooked starch has a significantly higher retention rate in fissures than liquid sugars.

- 600 Species: The approximate number of bacterial species living in the average human mouth.

The Enzymatic Process: How Starch Becomes Sugar

To understand why pasta causes cavities, we have to look at digestion. Most people believe digestion begins in the stomach. As a restorative dentist, I can tell you it starts the moment you chew. The oral cavity is a complex chemical processing plant.

The Role of Salivary Amylase

Your saliva contains a powerful enzyme called salivary amylase (also known as ptyalin). Its sole purpose is to begin the process of starch hydrolysis. Pasta is composed of long chains of glucose molecules called amylose and amylopectin.

These are polysaccharides. To the bacteria in your mouth, these large chains are too big to eat directly. They need the chains broken down into manageable bites. This is where amylase comes in.

As you chew your spaghetti, salivary amylase mixes with the food bolus. It cleaves the glycosidic bonds holding these chains together. Within seconds, the complex starch is converted into maltose, a disaccharide. Further breakdown converts this into glucose.

This is why if you chew a piece of plain bread or pasta for a long time, it starts to taste sweet. That sweetness is the literal release of sugar into your oral environment. You are manufacturing sugar in your mouth with every chew.

Polysaccharides vs. Disaccharides

From a nutritional standpoint, we are often told that complex carbohydrates (polysaccharides) are better than simple sugars. For gut health and insulin regulation, this is generally true. But for oral health, the distinction is much less clear.

Because cooked pasta is soft and easily hydrolyzed, the conversion from “complex” to “simple” happens rapidly right on the tooth surface. Unlike a raw carrot, which requires heavy mechanical chewing and contains little fermentable substrate, pasta provides a near-instant fuel source. The cariogenic potential of pasta lies in this efficiency.

It delivers sugar to bacteria while simultaneously sticking to the tooth. This ensures the bacteria have ample time to consume it. It is a perfect storm of fuel delivery and retention.

The Microbiology of Decay: Who is Eating Your Pasta?

Your mouth is an ecosystem. When you feed yourself, you are also feeding the billions of microorganisms that live on your teeth. Understanding pasta in dental terms requires us to look at the specific bacteria that thrive on this food source.

The Primary Culprit: Streptococcus mutans

The bacterium Streptococcus mutans is the arch-nemesis of a healthy smile. It is an acidogenic (acid-producing) and aciduric (acid-tolerating) organism. This means it makes acid and can survive in the acid it makes.

When salivary amylase breaks pasta down into glucose, S. mutans metabolizes that glucose for energy. The waste product of this metabolism is lactic acid. This acid is what physically dissolves the hydroxyapatite crystals that make up your enamel.

It is not the pasta itself that drills holes in your teeth. It is the metabolic waste of the bacteria that just ate your pasta. You are essentially feeding a colony of acid-producing factories.

The Role of the Biofilm (Plaque)

We often refer to plaque as “fuzzy stuff” on the teeth. In clinical terms, it is a dental biofilm. This is a highly organized community of bacteria embedded in a sticky matrix.

Here is the dangerous part regarding starch. S. mutans uses the sucrose and starch byproducts not just for food. It uses them to build extracellular polysaccharides (glucans). These glucans act like biological glue.

They make the biofilm thicker and stickier. This creates a protective dome over the bacterial colony. This dome protects the bacteria from your saliva and traps the lactic acid against the tooth surface.

Pasta starch contributes significantly to the volume and stickiness of this matrix. It makes the biofilm harder to remove with just water or tongue movement. The starch reinforces the structural integrity of the plaque.

The Stephan Curve: Visualizing the Acid Attack

In dental school, one of the first concepts we study is the Stephan Curve. This graph visualizes what happens to the pH level of dental plaque after consuming fermentable carbohydrates. It is the gold standard for understanding decay risk.

The Critical pH Threshold (5.5)

The resting pH of a healthy mouth is around 7.0 (neutral). Your enamel is the hardest substance in the human body. However, it has a specific chemical weakness.

When the pH drops below 5.5—the critical pH—demineralization occurs. Calcium and phosphate ions begin to leach out of the tooth structure. The tooth effectively begins to melt on a microscopic level.

When you take a bite of pasta, the bacteria produce acid almost instantly. Within 3 to 5 minutes, the pH in your plaque drops from 7.0 to below 5.5. You are now in the “danger zone” where the tooth is actively dissolving.

Duration of the Attack

This is where the concept of oral clearance becomes vital. If you were drinking a sugary soda, the liquid washes over the teeth and is swallowed. The pH drops, but saliva can rinse it away relatively quickly.

Pasta is different. Because it is a retentive food, it stays physically stuck to the teeth. It takes saliva approximately 20 to 40 minutes to buffer that acid and raise the pH back above 5.5.

However, if there is pasta stuck between your molars, it acts as a slow-release capsule of sugar. The pH may stay depressed for hours. This is why “grazing” on pasta salad throughout an afternoon is far more damaging than eating a large bowl in one sitting.

Retention and Oral Clearance: Why Pasta is Unique

Not all carbohydrates behave the same way physically. The retention of food particles is a major variable in cariogenicity (the ability to cause cavities). Liquid sugars wash away; starches stick.

The “Stickiness” Factor

Cooked starch forms a gelatinous paste. In dentistry, we look at how much force is required to remove a food substrate from the interproximal (between teeth) areas. Pasta scores very high on retention.

It packs into the deep grooves (fissures) of the molars. It also wedges into the tight contact points between teeth. Once packed into a fissure, the tongue cannot reach it.

Saliva flow is restricted in these tight spaces. This creates a micro-environment where the acid attack can continue undisturbed. This leads to what we call “pit and fissure caries.”

Al Dente vs. Overcooked: Does Texture Matter?

Here is a nuance that many general nutrition articles miss. The texture of the pasta changes its enzymatic breakdown rate. Pasta cooked al dente (firm to the bite) has a tighter starch gelatinization structure.

It requires more mechanical chewing and breaks down slightly slower than overcooked, mushy pasta. Soft, overcooked pasta has a higher surface area available for enzymatic attack. It becomes a sticky paste much faster.

From a dental perspective, al dente is marginally safer. It is less likely to adhere immediately as a paste. However, it is still a fermentable carbohydrate that requires removal.

Dr. Rossi’s Expert Insight

Many patients ask if rinsing with water is enough. While water helps, it cannot dissolve the dental biofilm or the gelatinized starch paste stuck in your molars. Think of it like trying to rinse peanut butter off a plate with just running water. You need mechanical friction (brushing/flossing) to truly dislodge it.

Analyzing the Cariogenic Potential of Different Pastas

Not all pasta is created equal. While the marketing on the box focuses on calories or gluten, we need to focus on the cariogenic potential. This involves looking at the starch composition, fiber content, and how likely it is to stick to your teeth.

| Pasta Variety | Glycemic Index (GI) | Oral Retention Risk | Saliva Stimulation | Dental Verdict |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Refined White | High | High (Very Sticky) | Low | High Risk: Rapid conversion to sugar and high retention. |

| Whole Wheat | Moderate | Moderate/High | High | Moderate Risk: Fiber stimulates saliva buffer, but starch remains fermentable. |

| Lentil/Chickpea | Low | Moderate | High | Lower Risk: Higher protein content buffers acid; less fermentable starch. |

| Gluten-Free (Rice) | High | High | Low | High Risk: Rice starch is highly fermentable and often stickier than wheat. |

| Konjac/Shirataki | Zero | Low | High | Neutral: Contains no fermentable carbohydrates for bacteria. |

The Whole Grain Myth in Dentistry

There is a pervasive myth that whole wheat pasta is “safe” for teeth. While whole grains are excellent for systemic health, we must clarify their role in the mouth. Whole wheat pasta still consists primarily of starch.

While the fiber content requires more chewing, which produces more saliva, the starch hydrolysis process still occurs. The bacteria do not care if the glucose came from white flour or whole wheat. They metabolize it all the same.

Do not fall into the trap of thinking you can skip flossing because you ate whole wheat spaghetti. The cariogenic potential is reduced compared to white flour, but it is not eliminated. You still have a retentive carbohydrate stuck in your teeth.

The Gluten-Free Trap

Many patients assume “gluten-free” means healthier in all aspects. For teeth, gluten-free pasta can sometimes be worse. These products often rely on rice flour or corn flour as a base.

Rice starch, in particular, is extremely sticky when cooked. It adheres tenaciously to the enamel surface. Furthermore, some gluten-free binders used to mimic the texture of wheat can increase the viscosity of the food bolus.

This makes oral clearance even more difficult. If you are eating gluten-free for medical reasons, you must be extra vigilant about your oral hygiene. The retention factor is often higher than with traditional semolina pasta.

The Synergy of Sauces: The Starch-Sugar-Acid Triad

We rarely eat plain pasta. The sauce you choose can either mitigate the damage or exacerbate the acid attack. When we analyze pasta in dental terms, we must consider the entire chemical bolus.

Tomato-Based Sauces (Acid on Acid)

Marinara and other tomato-based sauces present a double threat. First, tomatoes are naturally acidic (often pH 4.0-4.5). Second, many commercial sauces have added sugar to cut the acidity.

When you combine this with the pasta, you are introducing an extrinsic acid (erosion from the sauce). You are also fueling the bacteria to create intrinsic acid (caries from the starch). This creates a synergistic effect.

The enamel is softened by the sauce, making it more susceptible to the bacterial acid attack. This is why enamel demineralization is common in patients with high acidic dietary intake. The pasta sticks the acid to the tooth like a poultice.

Cream-Based Sauces and Fats

Surprisingly, a heavy Alfredo or carbonara sauce may be safer for your teeth than a light marinara. Fats, such as those found in cheese, cream, and olive oil, are hydrophobic (water-repelling).

They can coat the tooth surface. This creates a temporary barrier that makes it difficult for the starch to adhere. Additionally, cheese contains casein and calcium.

These elements can help buffer the pH in the mouth. They aid in the remineralization of tooth enamel. From a strictly dental perspective, the fat content acts as a protective factor against retention.

The Pesto Advantage

Pesto is perhaps the most tooth-friendly sauce option. It is primarily composed of basil, pine nuts, and olive oil. It is low in fermentable sugars and non-acidic.

The high oil content lubricates the teeth, significantly reducing the retention of the pasta starch. It also lacks the erosive potential of tomatoes. If you are prone to cavities, switching to oil-based sauces like pesto or aglio e olio is a smart clinical move.

Starch Retrogradation: The Science of Leftovers

There is a fascinating chemical change that happens when pasta cools down. This process is called retrogradation. It changes the molecular structure of the starch.

Resistant Starch Formation

When you cook pasta and then cool it down (like in a pasta salad), the amylose molecules recrystallize. They form a structure known as “resistant starch.” As the name implies, this starch is resistant to digestion.

It resists the enzymatic action of salivary amylase. Because the enzyme cannot easily break it down into glucose in the mouth, there is less fuel for the bacteria. The cariogenic potential drops.

Even if you reheat the pasta, some of this resistant structure remains. Therefore, eating leftover pasta or cold pasta salad is chemically less damaging to your teeth than eating it fresh off the boil. It feeds your gut bacteria rather than your oral bacteria.

Dr. Rossi’s Evidence-Based Hygiene Protocols

Knowing the risks does not mean you must banish pasta from your life. As a clinician, I believe in management over restriction. Here are the specific protocols I recommend to my patients to neutralize the effects of pasta in dental terms.

The “Wait to Brush” Rule

This is the most common mistake patients make. After eating a bowl of pasta with tomato sauce, your enamel is softened by the acid. If you brush immediately, you are essentially scrubbing away microscopic layers of your tooth structure.

This is called abrasion. You must wait at least 30 to 60 minutes after eating. This gives your saliva time to buffer the acid and re-harden the enamel.

In that interim period, use chemical buffering rather than mechanical abrasion. Do not take a stiff bristle brush to a softened surface. Patience is key to enamel preservation.

Immediate Interventions

If you cannot brush right away, what should you do? Here is a hierarchy of interventions:

- 1. Vigorous Water Rinse: Swishing water under pressure helps clear loose debris. It also dilutes the ambient acid in the mouth. It is not perfect, but it is a good first step.

- 2. Xylitol Gum: Chewing gum sweetened with Xylitol stimulates salivary flow. Saliva is your body’s natural defense. It is rich in bicarbonate (which neutralizes acid) and calcium. Xylitol also inhibits the growth of Streptococcus mutans.

- 3. The Cheese Finish: The French tradition of a cheese course is excellent for dental health. Eating a small piece of hard cheese (like aged cheddar or parmesan) raises the pH of the plaque. It provides casein phosphopeptide (CPP) to protect the teeth.

Flossing is Non-Negotiable

Brushing cleans the smooth surfaces of the teeth. However, pasta starch is notorious for lodging in the interproximal spaces. These are the areas where teeth touch.

A toothbrush cannot reach these contact points. If you do not floss after a pasta meal, that starch will remain there. It will ferment for 24 hours or more.

This leads to “interproximal decay,” which often requires complex fillings or crowns to fix. You must mechanically disrupt the biofilm between the teeth. Floss is the only tool that effectively achieves this.

The Mouth-Body Connection: Glycemic Load and Periodontal Health

The impact of pasta extends beyond cavities. We must consider the soft tissues—the gums. There is a strong, bidirectional link between high-glycemic diets and periodontal disease.

Insulin Spikes and Gum Inflammation

Refined pasta has a high glycemic index. Consuming it causes a rapid spike in blood glucose and insulin. Research has shown that systemic inflammation caused by high blood sugar exacerbates the inflammatory response in the gums.

Patients with diets high in refined carbohydrates often present with more aggressive gingivitis. They show more periodontal inflammation than those on low-glycemic diets. The body becomes hyper-reactive.

When the body is in a state of chronic inflammation due to diet, the immune response in the gums changes. It begins to destroy gum tissue and bone faster in response to the dental biofilm. Controlling your carb intake is not just about saving your teeth from holes; it is about saving the foundation that holds them in place.

The Role of Saliva Quality

Systemic health also dictates saliva quality. A diet high in sugar and starch can alter the composition of your saliva. It may become more acidic and less effective at buffering.

Furthermore, dehydration affects saliva flow. Pasta dishes are often high in sodium, which can lead to transient dehydration. This reduces salivary volume (xerostomia).

Without adequate saliva flow, the clearance of starch is compromised. The acid attack lasts longer. Staying hydrated while eating pasta is a simple way to help your body clear the food debris naturally.

Pediatric Considerations: The “Mac and Cheese” Syndrome

We cannot discuss pasta without mentioning children. Pasta is often a primary food group for toddlers and young kids. It is soft, bland, and easy to eat.

Primary Teeth Susceptibility

Primary (baby) teeth have thinner enamel than permanent teeth. The pulp chamber (nerve) is also larger relative to the tooth size. This means that decay can progress from the surface to the nerve much faster in a child.

A diet heavy in sticky pasta can devastate a child’s dentition. We often see “interproximal lesions” in children who graze on pasta or crackers. Parents must be vigilant.

If your child eats pasta, ensure they are drinking water with it. Do not let them go to bed with unbrushed teeth after a pasta dinner. The starch will sit on the teeth all night, causing significant damage.

Summary and Key Takeaways

We have defined pasta in dental terms not as a simple dinner option, but as a complex interaction of chemistry and biology. It involves starch hydrolysis, bacterial metabolism, and acid production. The key to maintaining oral health while enjoying pasta lies in understanding the science.

Remember the Stephan Curve. Every time you eat pasta, your mouth becomes acidic for upwards of 30 minutes. The stickier the pasta, the longer that acid remains. Your goal is to reduce the frequency of these attacks and aid your body in clearing the debris.

Choose your sauces wisely. Opt for oil-based or cream-based sauces over sugary tomato ones. Embrace the “cheese finish” to neutralize acid naturally.

Most importantly, respect the mechanical necessity of cleaning. Water alone will not remove the sticky starch paste. You must brush and floss to physically remove the fuel source from the bacteria.

By understanding the biochemistry of your meal, you can protect your smile. You can enjoy your fettuccine without fear of the drill. It is all about managing the environment of your mouth.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the clinical definition of ‘pasta in dental terms’?

In clinical dentistry, pasta is defined as a retentive fermentable carbohydrate. It is a complex polysaccharide that undergoes rapid starch hydrolysis in the oral cavity. When mixed with salivary amylase, it breaks down into simple sugars that fuel acidogenic bacteria within the dental biofilm, leading to enamel demineralization.

How does salivary amylase transform savory pasta into a cavity risk?

Salivary amylase, also known as ptyalin, begins the process of chemical digestion the moment you chew. It cleaves the glycosidic bonds in pasta starch, converting complex polysaccharides into maltose and glucose. This process essentially manufactures sugar directly on the tooth surface, providing an immediate fuel source for cariogenic bacteria like Streptococcus mutans.

What role does the Stephan Curve play in pasta consumption?

The Stephan Curve illustrates the drop in plaque pH after eating. When you consume pasta, the pH in your mouth typically falls below the critical threshold of 5.5 within minutes. At this acidic level, the hydroxyapatite crystals in your enamel begin to dissolve. Because pasta is highly retentive, the pH can stay in this ‘danger zone’ for 20 to 40 minutes or longer.

Why is the ‘retention’ of pasta more dangerous than liquid sugar?

Unlike liquid sugars that are quickly cleared by saliva, cooked pasta forms a gelatinous paste that adheres to the tooth’s pits, fissures, and interproximal contact points. This high retention rate increases the oral clearance time, meaning the bacteria have a prolonged period to produce lactic acid, which significantly increases the risk of pit and fissure caries.

Is whole wheat pasta safer for dental enamel than refined white pasta?

While whole wheat pasta is better for systemic health, its cariogenic potential remains significant. Although the higher fiber content may stimulate more saliva during mastication, it still consists of fermentable starch that undergoes hydrolysis. The bacteria in your biofilm metabolize the resulting glucose regardless of whether the source was refined or whole grain.

Does cooking pasta ‘al dente’ provide any oral health benefits?

Yes, from a dental perspective, al dente pasta is marginally safer. It has a tighter starch gelatinization structure and lower surface area for enzymatic attack compared to overcooked, mushy pasta. Overcooked pasta becomes a sticky paste much faster, which increases its adherence to the enamel and makes it harder for saliva to wash away.

How do tomato-based sauces exacerbate the damage caused by pasta?

Tomato-based sauces create a ‘double threat’ of erosion and caries. The natural acidity of tomatoes (extrinsic acid) softens the enamel, while the added sugars and pasta starches fuel the production of bacterial acid (intrinsic acid). This synergistic effect accelerates the demineralization process more than eating plain pasta would.

Why should I wait 30 to 60 minutes to brush after eating a pasta meal?

Brushing immediately after an acidic pasta meal can cause dental abrasion. The acids from the sauce and bacterial metabolism temporarily soften the enamel. If you brush too soon, you may mechanically scrub away microscopic layers of your tooth structure. Waiting allows your saliva to buffer the acid and facilitate the reminerilization of the enamel.

Can eating cheese after pasta really help prevent cavities?

Absolutely. Finishing a meal with a hard cheese like Parmesan stimulates salivary flow and introduces calcium and casein phosphopeptides (CPP) into the oral environment. These elements help neutralize the acidic pH and provide the necessary minerals for the reminerilization of tooth enamel, effectively counteracting the acid attack from the carbohydrates.

What is starch retrogradation and how does it affect cariogenicity?

Starch retrogradation occurs when cooked pasta is cooled, causing the starch molecules to recrystallize into ‘resistant starch.’ This form of starch is more resistant to salivary amylase, meaning it breaks down into simple sugars more slowly in the mouth. Consequently, cold pasta or reheated leftovers often have a lower cariogenic potential than fresh pasta.

Why is flossing specifically mentioned as non-negotiable after eating pasta?

Pasta is notorious for packing into the interproximal spaces where teeth touch. A toothbrush cannot reach these tight areas to remove the sticky starch paste. If left undisturbed, this starch will ferment and fuel the dental biofilm for hours, leading to interproximal decay, which often requires more invasive restorative treatments like crowns or fillings.

Why are children’s teeth more susceptible to ‘Mac and Cheese’ syndrome?

Primary (baby) teeth have much thinner enamel and relatively larger pulp chambers than permanent teeth. When children frequently consume sticky, starchy foods like pasta, the resulting acid attacks can penetrate the thin enamel and reach the nerve much faster. This makes pediatric patients particularly vulnerable to rapid-onset decay from retentive carbohydrates.

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical or dental advice. The information regarding pasta in dental terms and oral biology is based on current dental research but should not replace professional diagnosis or treatment. Always consult with a qualified dentist regarding your specific oral health needs and before making significant changes to your diet or hygiene routine.

References

- American Dental Association (ADA) – ada.org – Provides clinical guidelines on the cariogenicity of fermentable carbohydrates and starch.

- National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) – nidcr.nih.gov – Source for data on the Stephan Curve and enamel demineralization processes.

- Journal of Dental Research – “The Role of Starch in the Pathogenesis of Dental Caries” – A peer-reviewed study on how amylase interacts with cooked starches.

- World Health Organization (WHO) – who.int – Technical information on the relationship between free sugars, starches, and global oral health trends.

- British Dental Journal – “Food Retention and Oral Clearance” – Research regarding the physical properties of pasta and its adherence to tooth surfaces.

- Journal of Periodontology – “Dietary Glycemic Load and Systemic Inflammation” – Investigates the link between high-carb diets and gum disease.